It gets easier, but it never gets easy

Part 1 of a series about alcohol, addiction, and recovery

This is Part 1 of a series about alcohol, addiction, and recovery. I realized as I started writing about these subjects that I have much more to say than can fit into one piece. This essay focuses on my struggles with alcohol and what influenced my decision to quit drinking in October of 2020. I would love to hear from readers about any specific questions or topics you’d like to discuss in future installments of this series.

I didn’t know my last drink would be the last. It was the day after my 39th birthday, and I was celebrating with my siblings and our significant others. Only six months into the COVID-19 pandemic, we sat, shivering, around an outdoor table overlooking the Potomac River. I had a couple of rum cocktails. My coat sleeves covered the rough red skin on my wrists, the eczema I knew was caused by excessive drinking and that I’d tried to resolve in every way other than quitting.

I’d taken several long breaks from drinking before, each time hoping to finally master the art of moderation. I always returned to it with naïve hope (or denial) because the idea of stopping forever seemed impossible. Surely I just needed the right strategy to tame my ravenous desire and become a “normal” drinker.

Alcohol was rarely around when I was growing up. Occasionally my parents would have a glass of shandy, half beer and half ginger ale. In high school, I had almost no interest and was actually pretty nervous about drinking. When I first got drunk at 17 on a trip back to my hometown, it didn’t feel fun, and I mostly remember the wicked hangover, riding the T through Boston at sunrise as the city spun dizzily around me.

It was in college that my relationship to drinking shifted. I turned 18 a month after arriving at Mary Washington College in Fredericksburg, Virginia, where I felt wildly out of place (a feeling that never entirely went away in the two years I spent there). My roommates threw a small surprise party, which touched me even though I felt like an alien around them and their conversations about church, country music, and high school boyfriends. The next morning, I realized how drunk I’d gotten when I ran into someone I’d met at the party and didn’t remember him at all. He grinned kindly and recounted the story of our meeting, and in his gentle amusement was something I’d longed to find: an escape from myself. A persona that was fun and approachable and the life of the party, the opposite of the girl that people tended to query with concern: “Why are you so quiet?”

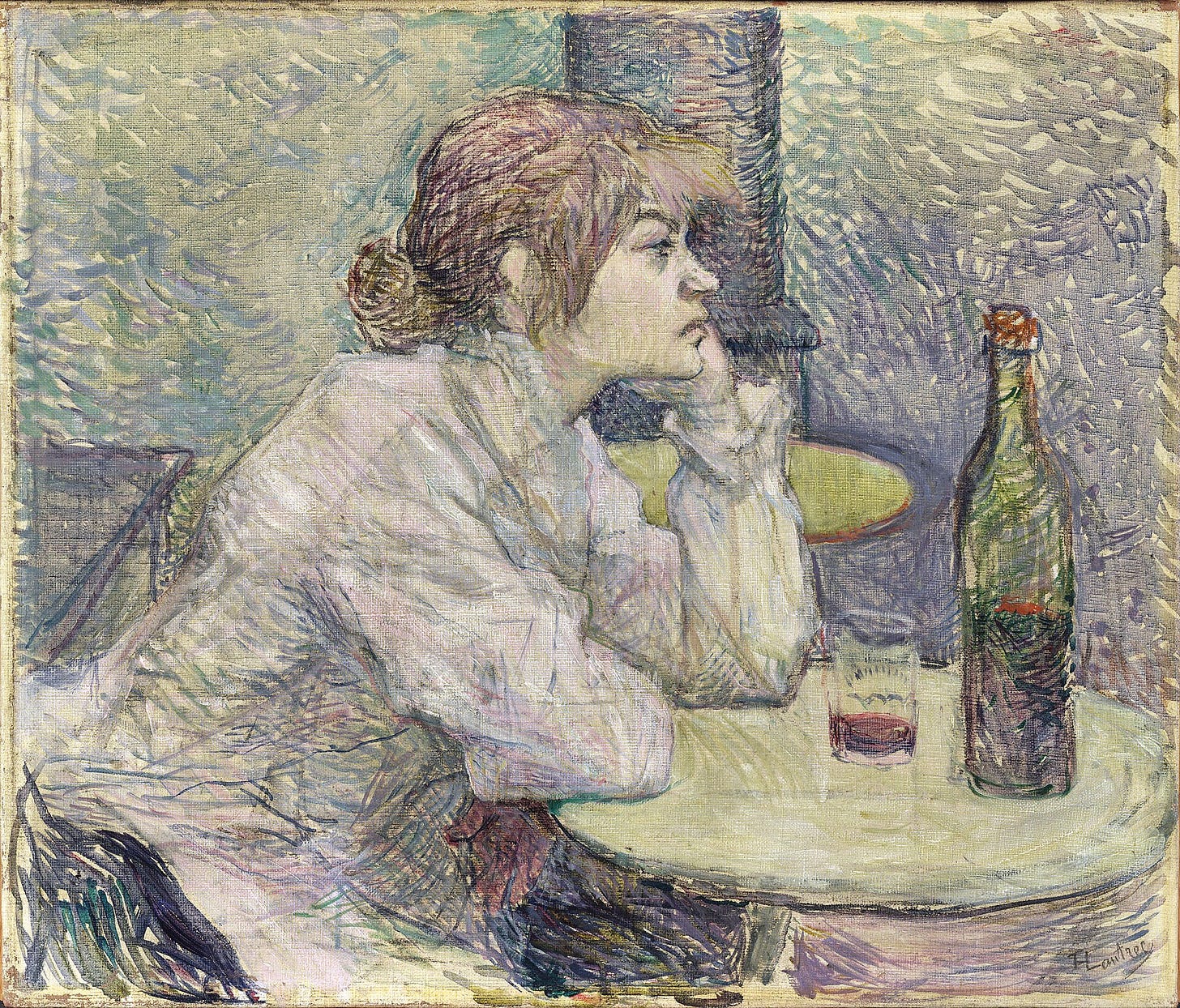

The guy I didn’t remember became one of my closest friends at MWC, part of a group of fellow misfits who, as it happened, mostly didn’t drink. But I’d been quickly seduced by the transformation that alcohol seemed to offer, and from then on I took every opportunity to chase it. My drinking was not dainty; it was aggressive, with the intent to obliterate. Some nights I was barely able to walk back to my dorm. Instead of dating, I settled for inebriated hookups, often with guys I didn’t even like. Most people I knew drank to excess on a regular basis, but even friends I partied with would sometimes tell me that my behavior worried them. My mom worried too, though I tried to hide the extent of my drinking and to dismiss her concerns because she grew up in India, where alcohol is not the focus of social life.

I wrote a poem recently that begins,

Ask me how many places I’ve hidden bottles

In duffel bags and car trunks, closets and trash cans

In pockets, in plain sight

In my own forgetting

The elixirs that temporarily freed me from my inhibitions left a lot of evidence that I went to great lengths to hide. When I left MWC after my sophomore year and moved back home, I started drinking to fall asleep at night. I’d sneak honey brown ales from the fridge in the basement, or buy a six-pack of cheap light beer and retrieve it from my car after everyone was asleep, squirreling away the empty bottles in the trunk until I could dispose of them in some anonymous location.

I left college because I’d lost the ability to hold everything together. When I was 15, my abusive stepfather was removed from our home by restraining order. This was followed by a years-long custody battle and repeated incidents of violence, which continued to affect me deeply after I left home. During my freshman year at MWC, I had to travel back to Maryland to testify against him in court. When I was away at school, I was heavy with the weight of what was happening at home and felt powerless to help. In addition to drinking all the time, I was self-harming in other ways and grappling with an eating disorder. I’d always been a good student, and I hardly recognized myself as I stopped going to class or turning in assignments.

I use the term stepfather now for lack of a better word, but when I was a child and a young adult he was just my father, having legally adopted me when he and my mother got married. Despite his long history of abuse, he was allowed unsupervised visits with my siblings, who were too young to have a say in the matter. When I moved back home, I accompanied them and protected them as much as I could when they stayed at his house. He disowned me for standing up to him, and though there was no love lost, a wound exists in me where a father should have been. It’s not a coincidence that my drinking escalated during this time.

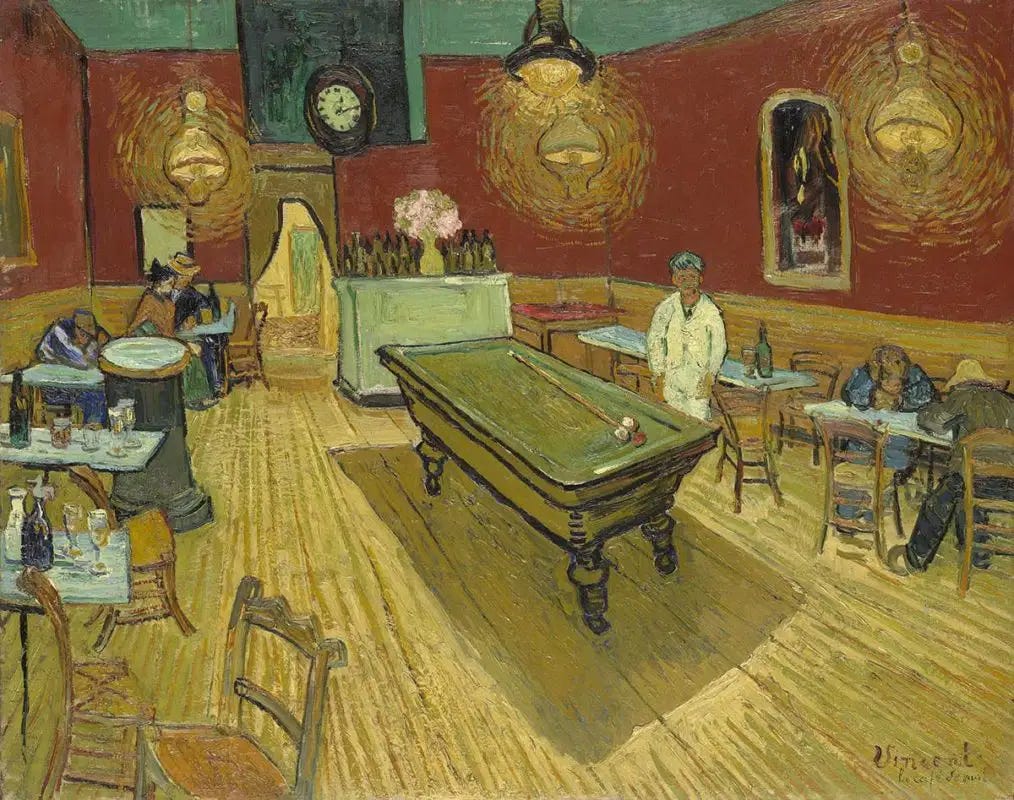

For 21 years, I turned to alcohol in all kinds of circumstances. I drank to cope with a decade of isolation and intimate partner violence, and I drank through relationships that were caring and supportive. I drank to make friends, rarely hanging out with anyone without alcohol present. I drank before I went out and after I got home. I drank at family gatherings. I drank to assuage my anxiety about playing music and networking at open mics. I drank to drown despair, to relieve boredom, to blunt anger, to heighten joy. I drank in order to enjoy the life I thought I should want, busy and bubbly and brightly lit.

I’ve been quiet, reserved, and introverted since I was a kid, and it was clear to me early on that people regarded this as odd. It wasn’t only my stepfather, who accused me of being “anti-social” when I didn’t want to attend events with his friends or colleagues. It was everyone who found my shyness so strange that they were compelled to comment on it. I understand now that people do this out of their own discomfort with silence, but I’m sensitive to it all the same. More than anything else, more than all the trauma I’ve survived, it was the idea that I needed to change to fit in that drove my drinking.

It is why I sometimes still long to drink.

The year I quit (2020), Jason Isbell released his album Reunions, which includes a song called “It Gets Easier”. Isbell is one of my favorite songwriters, and I admire his openness about his personal struggles, including his alcoholism and sobriety. Knowing he’d been sober for years, it was such a gift in my early days to hear him sing, “It gets easier, but it never gets easy.” To see my own experience reflected in the opening lines: “Last night I dreamt that I’d been drinking / Same dream I have about twice a week.” (Followed by this brilliance: “I had one glass of wine / I woke up feeling fine / That’s how I knew it was a dream.”)

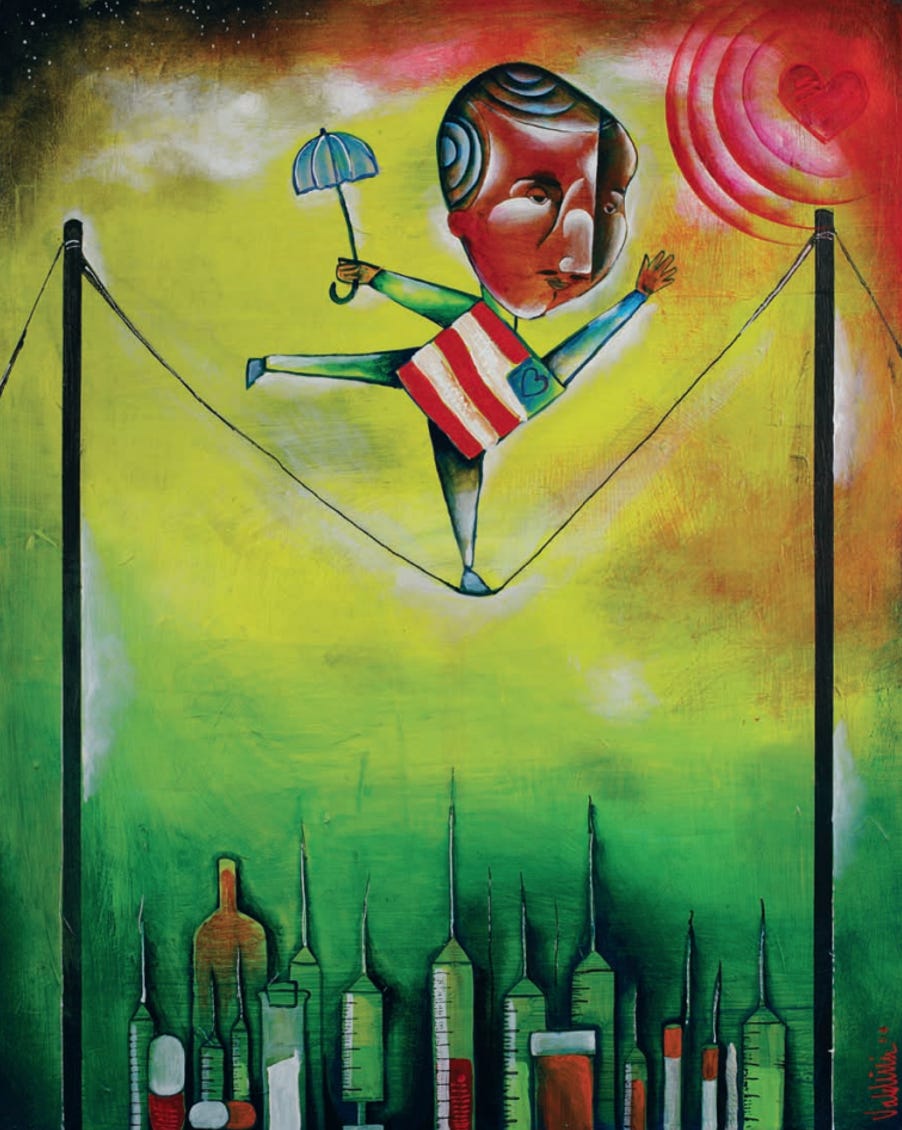

It remains a comfort, a precious reminder that it’s okay for it to be hard. To choose recovery is to undertake a difficult journey, to enter the underworld to rescue ourselves.

I couldn’t make this choice before I was ready. It took years of introspection, experimentation, and contemplation. Looking back, I think the most helpful practices for me during this time were:

Taking breaks from drinking. They never helped me to moderate, as I’d hoped, but they taught me so much. I learned that I was capable of living fully without altering my personality - that I could still socialize, meet new people, date, and perform on stage as I was (even if it was awkward). I learned that the painful eczema I’d developed all over my body almost disappeared in the absence of alcohol. I learned that each time I started again, I ended up drinking more than I ever had before. I had intended to take another break in October 2020, and sometime during that month I realized I was ready to leave it behind for good.

Reading other people’s stories. I was very secretive about this, which is kind of funny in retrospect - slinking out of the library trying to conceal the covers of alcoholic memoirs like they were bottles of booze, browsing the Stop Drinking forum on Reddit for hours in Incognito mode. I found the Reddit forum to be one of the best places to read about other people’s experiences because they were so raw and unedited, and because others in the community responded with so much understanding and grace. A couple of the memoirs I really liked were Drinking: A Love Story by Caroline Knapp and Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget by Sarah Hepola, but the book that made me feel for the first time like quitting was possible was This Naked Mind by Annie Grace.

This Naked Mind was different from any other book I’d read. It’s part memoir, but it’s also a nuanced and well-researched exploration of our cultural attitudes about alcohol. Grace shows that it’s our unconscious beliefs that keep us drinking even when we consciously want to cut back or stop entirely. She writes:

When you make a conscious decision to cut back on alcohol, your unconscious desires remain unchanged. You have unknowingly created an internal conflict. You want to cut back or quit, but you still desire a drink and feel deprived when you do not allow yourself one.

Also, the unconscious mind often works without the knowledge or control of the conscious mind. Studies from as far back as 1970 prove our brains actually prepare for action ⅓ of a second before we consciously decide to act. (p. 27)

So what can we do? . . . We need to bring unconscious experiences, observations, assumptions, and conclusions into conscious thought. This allows your unconscious to change. (p. 33)

This is exactly what Grace does in the book. With compassion, she identifies the most common myths about alcohol and challenges them. If you drink, she encourages you to simply start to notice where your beliefs about alcohol conflict with your lived experiences of it.

Over the next day, notice how many messages you are exposed to about the “pleasures” and “benefits” of alcohol. Look around—from your friends to what you watch on television, almost everything in our society tells you, both consciously and unconsciously, that alcohol is the “elixir of life,” and without it your life would be missing a key ingredient. (p. 34)

As someone who often drank to be more outgoing, I needed to question my assumption that alcohol was helping me in social situations. It was such a relief when the buzz entered my bloodstream, diluting my social anxiety and loosening my tongue. As I had more sober social experiences, though, I began to notice that people are not actually more interesting or fun or charming when they drink, as I was certain that I was. Drinking didn’t change me for the better; it just made me louder and less self-conscious because it numbed my awareness of both my internal and external environments. Grace’s perspective that shyness is natural and doesn’t need to be eliminated was so validating for me:

Shyness and introversion are not negative, yet we’ve been conditioned to think they are. These emotions protect us, helping us to navigate life with grace. It’s not a lot of fun to be shy, but it’s normal. Everyone feels it. In Susan Cain’s book Quiet, the Power of Introverts in a World that Can’t Stop Talking, she discusses what a gift it is to listen, a gift to the people we are listening to and to ourselves. (p. 109-110)

She also observes that since she quit, she’s “ready to have fun” at social events before her friends who drink. I remember so well the feeling of arriving somewhere and not being able to relax or enjoy myself until I’d had a drink or two. I half-joke now that there’s no escape from my own awkwardness, but there is liberation in showing up as I am.

There is also beauty in being fully present, as challenging as it can be. A huge source of shame when I was drinking was the frequency with which I blacked out. It embarrassed me when friends referenced conversations or stories that I couldn’t remember, and I was constantly anxious about how I might have behaved or what I might have said. It was sad to wake up the morning after a special occasion like a wedding and realize I had almost no memory of it. Being able to recall the details of my own experiences is worth giving up the ease of oblivion. I can hear my own voice and honor my needs, even if they are out of sync with the crowd. To leave the party early when I’m ready to go is an act of self-love and acceptance.

One of the biggest beliefs that This Naked Mind upends is that alcoholics are inherently different from other people who drink. Grace explains how the false binary of alcoholics vs. regular drinkers actually prevents most people from examining their own habits.

Instead of treating alcohol with caution because we know it to be dangerous and addictive, we reassure ourselves that we are different from those flawed people we know as alcoholics . . .

We see many people who seem to “control” their drinking and can “take it or leave it.” So it’s difficult to understand why some people’s first sips launch them into full-blown dependence while others never reach that point. But it is not just alcoholics who systematically increase the amount they drink. Regular drinkers start off with just a few drinks and are soon consuming a nightly glass of wine. In fact, alcoholics start off as “regular” drinkers. In many cases it takes years for them to cross the indistinct line into alcoholism. (p. 46-47)

The alcohol industry is invested in this lie (“drink responsibly!”) because heavy drinkers account for the majority of their sales. Once you start to see it, you realize how much the culture of alcohol depends on selling a fantasy. The book addresses how the fine wine industry normalizes heavy drinking by framing the appreciation of wine as “refined”, and I’ve seen the same thing happen over the years with craft beer. With the steady stream of new beers on the market, I always had an excuse to drink, and I would often order the highest alcohol-by-volume options on the menu so I could appear to be drinking less than I really was.

I regret every time I drove after drinking too much. I never intended to, but alcohol impairs judgment so that we often don’t realize when we’re unable to drive safely. In the U.S. on an average night, one in ten drivers on the road is drunk. Half of fatal highway accidents involve alcohol.

Research shows no health benefits to consuming alcohol, despite the many popular articles claiming, for example, that red wine is good for your heart. There are lots of scientific studies showing the harms of alcohol, but these aren’t mentioned as often in mainstream publications. Alcohol is a major causal factor in disease, injury, and premature mortality. It alters the brain, contributing to depression and inhibiting the capacity to learn and solve problems. It impairs the immune system and increases the risk of cancer, even for light drinkers.

Seventy percent of violent incidents related to alcohol occur in the home, which I have experienced firsthand in abusive relationships. Alcohol abuse by parents affects children even in a generally loving household; it’s scary for them to see the adults who care for them in an altered state. When I was dating someone who had young kids, they hated that we drank every night and were very vocal about it. Their protests didn’t change our behavior, but it’s one of many occurrences over the years that unsettled me and stuck with me, like a pebble in my shoe. The slow accumulation of small inklings over time eventually coalesced into a larger knowing.

I used to smoke cigarettes. I quit nine years ago, also on my birthday, and I’m grateful for learning from that the importance of being ready to make a big change. This is why it’s so difficult to change solely for another person. My desire to be free of cigarettes had to be stronger than my desire to smoke, and now I want to be sober from alcohol more than I want to drink.

Tom Waits is another favorite artist of mine, a storyteller extraordinaire and musical innovator. He credits his wife, Kathleen Brennan, for saving his life by helping him to get sober, but he adds:

“But I had something in me, too. I knew I would not go down the drain, I would not light my hair on fire, I would not put a gun in my mouth. I had something abiding in me that was moving me forward. I was probably drawn to her because I saw that there was a lot of hope there.”

I attended a handful of A.A. meetings online and found them to be welcoming and affirming, but I haven’t followed any particular program. For me, being honest with the people in my life has been profoundly healing and gives them an opportunity to support me. I feel cared for when someone remembers that I don’t drink and is sensitive to that. As awkward as I may feel with my non-alcoholic beer or seltzer or tea, I also take immense pride in caring for myself in this way.

My creative practices have shepherded me as well. When I see videos of musical performances from before and after I stopped drinking, I’m amazed at the difference in my demeanor and energy. Even on my worst days now, there is a spark of life infusing my being that drinking had stolen from me. I connect more authentically with people and actually feel more comfortable on stage. I have the focus, clarity of thought, and confidence to take on an ambitious project like writing this newsletter.

The process of recovering from two decades of alcoholic drinking is also a continuation of work I was already doing to heal. I don’t think we talk enough about how intertwined trauma and substance abuse are (a topic I plan to focus on in a future essay in this series). This is what the concept of hitting rock bottom has meant for me: hands in the soil, tending to the roots of my pain, clearing space for new growth. Life always begins in darkness.

None of this is easy, but it is rewarding. It is real, whereas the existence I had constructed around alcohol was built on so much illusion.

I share my story as part of my own healing and as an offering to others. Many people have opened up to me about their own fears and concerns around their drinking habits, an experience echoed by Annie Grace.

If you wish you could stop after just a few, odds are so does your best friend. If you sometimes worry about drinking every day, chances are so does your partner. Alcohol addiction is so insidious because of how well we hide it, even from ourselves. We are ashamed to question our drinking. We worry that by asking a question we may be forced to quit drinking and live marginalized from society. (p. 174)

I have noticed a cultural shift since This Naked Mind was published in 2015 and since I had my last drink in 2020. There is less of a stigma attached to not drinking, and the “sober-curious” movement has exploded, which is why every brewery makes a non-alcoholic beer now. More people I know are using N/A beer to cut back on the amount of alcohol they drink. Studies show that Gen Z drinks far less than previous generations. We are such powerful influences on one another; our health and thriving is intimately connected whether or not we are aware of it.

My door is open to anyone who wants to talk. I’m not the life of the party, but I am a great listener.

Links and Recommendations

Here is a link to a free PDF copy of This Naked Mind by Annie Grace. I reread it as I was writing this essay and found that I needed to hear a lot of these ideas again. The information and statistics about alcohol that I reference are taken from this book, which cites a wealth of scientific sources in its endnotes.

There are some wonderful newsletters here on Substack that focus on recovery:

“It Gets Easier” by Jason Isbell. This song anchors me to all the reasons I no longer drink. Whenever Isbell mentions his sobriety at shows, there is an eruption of cheers and applause from the audience, and I know that in addition to showing our support for his journey, so many of us are celebrating our own.

An incredible piece of writing, Sarah. Thank you for sharing such an intimate and self-reflective story. Coming to the decision to embrace a clean and sober life is not an easy one. Doing so is even more difficult. It’s okay to want that drink, as long as you know how to avoid having it.

Keep writing about your journey. It’s inspiring to us all!

It takes courage to share your journey. You have shown forthright and brutal honesty in revealing your inner struggle, your acting out of the deep pain lodged in your heart and soul and psyche. I honor this brave attempt to put this out. I imagine it is cathartic for you but it is also an invitation to all those who struggle with any addiction to talk about their pain. The numbers of hurting souls, I imagine, are legion. Thank you for digging deep into your soul and sharing your raw vulnerability with others.